effluent

of the Superior Rhine at the west end of Lake Constance. In the background

the Untersee with the Reichenau island.

effluent

of the Superior Rhine at the west end of Lake Constance. In the background

the Untersee with the Reichenau island.(Photo: S.Luber, 1971)

Depending on where one begins or ends one gets a different story. Ours starts at Lake Constance, Rhine-kilometer zero. It ends at kilometer one thousand thirty-six in the North Sea. This 'story' is the story of the Rhine as a modern navigable waterway.

The attentive reader may ask, why Constance, why not Rheineck or Rorschach, where the Alpine Rhine flows into eastern Lake Constance that is regarded as part of the Rhine not just geographically, but also as Rheinsee that bears the etymological marks of the Rhein, with a Seerhein, and an abundance of boats. And if not from there why from the town of Constance, since navigation on the Rhine between Constance and Rheinfelden where dams block the way is only possible on a piecemeal basis.

As for the first question, the length of rivers is known since surveying

is practiced on a general scale. Although the division of rivers in pieces

of one kilometer length is in accordance with the actual distances measured,

the use of lies elsewhere. It serves above all as a means of orientation

to those who travel on it as to those who maintain the waterway. Therefore

the marking of kilometers would not make much sense along the Alpine Rhine.

Nobody shall guarantee that things stay as they are. It wouldn't be for

the first time that the route sections have been re-marked, usually in

connection with an adjustment of borders. Until the Congress of Vienna

the markings have been more or less up to the necessities of the respective

riverine state. When the Congress declared the Rhine an international

waterway, a cross-border arrangement loomed on the horizon. Still for

quite some time each state remained responsible for its part of the river.

Counting of kilometers began anew at every state border as a sign of sovereign

right. Which entailed some difficulties, since the border on the right

bank and the border on the left did not coincide. Manifestations of this

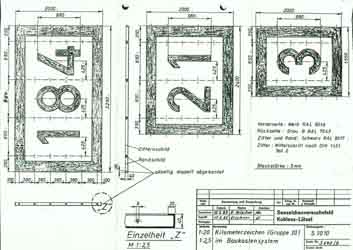

are still to be found, for instance in the so-called myriameter stones,

set up every ten kilometers on the banks of the Niederrhein and with indication

of elevation with reference to the Amsterdam Water Level.

Like other agreements on time or measures the 0-kilometer at Konstanz was a major achievement since markings now run through to the North Sea regardless of boundaries. And not without reason mark 0 is in Konstanz. It stands for the expectation that one day the Rhine will be navigable continuously from the North Sea to Lake Constance.

Even in 1959 there was hope that ships would travel between Rheinfelden

and Konstanz. There was even an Aare-Hochrhein Shipping Company. With

the building of the Grand-Canal d'Alsace between wars plans for a regulation

of the Hochrhein gained new momentum.

The distance between Basel and Konstanz is one of the most beautiful -

nowhere along the Rhine the landscape slopes right into the river - but

also the most difficult to prepare for safe shipping, only comparable

with the trajectory between Bingen and St. Goar. The river cuts into the

mountain sharply and flows through the narrow valley at a steep incline,

passing several cataracts, the most difficult of which is the  Rheinfall

at Schaffhausen. Most of these disappeared in lakes of hydro-electric

power dams. These were planned and built without locks, because the flow-rate

would have been too irregular for a guaranteed minimum water level. Moreover

a passage through the Rheinfall would have met the unsurmountable resistance

of the people of the area.

Rheinfall

at Schaffhausen. Most of these disappeared in lakes of hydro-electric

power dams. These were planned and built without locks, because the flow-rate

would have been too irregular for a guaranteed minimum water level. Moreover

a passage through the Rheinfall would have met the unsurmountable resistance

of the people of the area.

The Swiss whose navigation, apart from mountain rafting, has greatly been restricted the lakes, have been particularly skillful in using their watercourses as an energy resource. In 1866 the first hydroelectric dam was built in in the Rhine at Schaffhausen, followed by another dam in Rheinfelden in 1895-1898. If canalizing the Rhine was out of the question, developing it as an energy resource for the industry in the Northwest seemed a practicable compromise. Over the first half of the 20th century a number of hydro-power plants were built: Laufenburg (1908-14), Eglisau (1915-20), Ryburg-Schwörstadt (1927-32), Albbruck-Dogern (1929-33), Reckingen (1938-41), and Rheinau (1952-55).

The construction of the Great Alsace Canal that happened to begin a few kilometers south of Basle transformed the city into the main and only port of an otherwise landlocked country. Since Basle itself was for the greater part surrounded by neighbouring territory with not much of a hinterland to expand, it seemed only natural to take out of the drawer the old plans to canalize the Rhine upstream to Constance. Yet, before the plans could be seriously discussed, rails and road lent themselves as a more practical and less costly alternative. Before the ground could be broken, Rhine navigation that had been a promising means of transportation after WWII, had lost its appeal. The oil crisis, changes in international transportation policy, economic restructuring and rationalization led to stagnation in engineering projects with respect to inland navigation on such a geographically small scale. Reaching Lake Constance by water from Basle seemed a comparatively dead end. Construction of the dam in Grenzach-Wyhlen (1907-1912) and the Augst lock and the dam and lock in Birsfelden (1952-1955) remained the only projects that were put into place beyond Basle. Until further notice navigation ends at the bridge of Rheinfelden.

* * * *

The Superior Rhine between Constance, the 'town of the Council', and the twin cities of Rheinfelden is among the most mellow, if not the most beautiful of the Rhine. A claim that follows the natural course of the river's morphology between the Black Forest in the north and the foothills of the Alps in the south. Admittedly beauty is, to speak with Theodor Adorno, an exhausted special case. Currents flow better with decreasing resistance. Because of the dams that have turned the river into a succession of lakes the landscape has lost most of its asperity since the times of, lets say, Goethe, who wrote

towards their fall,

frothes he annoyed

step by step

to the abyss

etc.

| Alpenrhein |